There’s a recent episode of the Paré Paré podcast where the host Trevor and Karlos Williams discuss all things cars and watches. When Trevor asked Karlos about the intersection of the two, he responded, “If you like nice cars, more than likely you like nice watches. If you like nice watches, more than likely you like nice cars. They go hand in hand.” Sir, I couldn’t agree more. The connection has been around for decades, from sport racing and an integral role in movement evolution, to leisure and luxury lifestyle—so much so that collaborations between watch and automotive brands are infinite.

My own intertwined watch + car history began not only at the same time, but with the same person, my mom's brother. Uncle David's passion for cars hit me over the head before I entered kindergarten. Upon request, he recently sent me an excel spreadsheet with almost every car he’s owned. The final tally? 45. (He clarified he’s “missing a few.”) When I turned 8 years old, he purchased a Guards Red 1990 Porsche Carrera 2, which was, to me, the coolest car in the world. Even today it's high on my list. It had everything a sports car should. The black leather bucket seats were so low to the floor you could feel the engine hum, the tight 5-speed manual gearbox was a joy to use (as I was told, being 8), and the body style—a touch of racing aggression peppered into the daily driver simplicity of a non-turbo Porsche—helped set apart the 964 from other cars on the road. The body style has gone on to become one of the most highly sought-after models, though my uncle sold his long before it reached that status.

Passengering along on weekends to pick up family pizza in the C2 would unknowingly spark a lifelong love. By age 10, I wanted to learn how to drive, but my mom waited until I was 14 before letting me take her 2005 Mazda 3 hatchback for a lap around a parking lot. Once she let me behind the wheel, our “driving lessons” were every weekend; she let me practice every cornering technique I thought it could handle.

By then I’d started working at German Auto Specialists, my hometown specialty car shop outside Philadelphia that serviced vintage and new performance. Three days a week after school and full time during the summers, I mopped floors and changed oil, eventually learning technical tasks like changing tires and assisting the mechanics. John, the senior mechanic, who had a shaved head, stood tall at 5’10” with broad shoulders and a brain much smarter than he wanted anyone to believe, was a mentor to me. I was scared of working on certain tasks, knowing that, say, bleeding brakes incorrectly could lead to serious repercussions. John did his best to build my confidence while I remained constantly nervous I’d put the wrong fluid in the wrong hole, or hadn’t tightened a lug nut to the exact ft lbs necessary to keep it rolling safely down the highway.

Almost twenty years later, I’m heading upstate so we can do a rear brake swap on our car in J’s parents’ barn, aka her father’s pro-level, Euro-centric, racing car machine shop, these days more often used for family tune ups. (Brooklyn streets are hell on our rear springs, plus new calipers and rotors.) I am extra grateful that John’s management, and my own internalized anxiety, overcame a teenager’s reckless need for speed, forcing me to learn properly, slow down and process the schematics correctly without seriously endangering myself or anyone else.

My uncle's garage, too, has evolved. In 2000 the C2 was sold, making room for what would become his pride and joy: a 1972 Ferrari Dino GT. (The literal car, resold this year on BaT) If you care about cars, you may understand my feelings about this. The now-iconic GIF of Chris Tucker and Ice Cube in Friday? That was me.

Dave meticulously restored the car from the ground up, working with Algar Ferrari in Rosemont, PA, then owned by Bob Segal. They rebuilt the engine, stripped down the body and resprayed it in period-correct Ferrari Corsa Red, and reupholstered the leather interior in black and tan. The only custom mod? Opening up the exhaust pipes a bit for a louder sound. Otherwise, the car remained 100% stock. The Dino represented the chance to ride in something truly unique. Looking back now, I can better understand why I was so captivated. I knew it felt special at the time, but didn’t understand exactly why there was more to it than that. I remember most how it felt to ride in it: low (very low), and very loud. Though restored, the car was period-correct, meaning it had a near-racing suspension. The sound from the rear—the engine directly behind your head—was deafening. The V6, at 196 bhp, was not the most powerful engine ever made. It hardly matters. Between the ground positioning, the sound at your head, and the sharpness of the transmission, you were WELL AWARE you were flying, even at lower speeds. I distinctly remember a fascination with the gearbox. A classic Ferrari 5-speed, no boot to cover, just a beautiful shiny chrome knob and a narrow slot showing you exactly where the shifter was. The Dino was not forgiving. Every movement had to be deliberate. There was something inherently alluring about shifting that car, all about the intentional precision.

It also represented history. It was a 30-year-old car then, with the vintage plates to match. Though I couldn’t vocalize my obsession with the history of objects at age 14, I knew this car was special because of the life it had lived. It looked old, it looked luxurious and rare—because it was—but it displayed those characteristics romantically in a way that contemporary cars can’t.

Uncle Dave owned the Dino from 2004 to 2008. During that time, he also had a 1974 Triumph TR-6, a 1963 Porsche 356B Super 90 Coupe, a 2002 Boxster S as a daily driver, an E46 BMW M3, and, for the kids, a Land Rover Discovery. By 2008, he was itching for something more modern. The Boxster had some issues, and the Dino, while ridiculously special, wasn’t practical, even for a weekend car. The Triumph was a beautiful headache. He moved some things around at Algar Ferrari and walked out with a 2001 Ferrari 360 Modena in Nurburgring Silver, a 6-speed manual.

I was obsessed with that car in a completely different way than the Dino, but just as deeply. It was new, sleek, and undeniably fast. My first ride in it, at 16, felt like being in a pro race car. God bless my uncle for his unwavering commitment to owning manual cars, because when he shifted that 6-speed from 2nd to 3rd, it just took off. It was the first time I felt the sensation of being physically pushed back into my seat.

Being part of the Algar family meant attending car events with Dave, opening up a whole new avenue of culture for me: cars & coffee. Twice a month, we’d meet up with his friends to grab coffee and enjoy the cars on The Philadelphia Mainline. With that crowd, it wasn’t unusual for me to sit in an Enzo just a year after its release, or hear the complaints about owning a Testarossa, or a 512BB. For years, my entire life revolved around cars. I studied Ferrari like it was my job (thanks, Ferrarichat.com), attending every car event I could.

At 16, working at a performance car shop, I counted the days to have a license and a drive of my own. When a 1989 Honda Accord Coupe came my way, I resprayed it in black, put a lowering kit and some wheels on it. It was nothing special, but it was gifted and I loved slamming it around. I had that car for about 6 months until I could buy my boss’s old family car—a 1986 BMW 325e Coupe 5-Speed manual in maroon with a tan interior, with a hand crank (!) moonroof. I. Loved. That. Car. Was she the fastest (or even fast at all) on the road? She was not. But she was classy and drove smooth, with a manual gearbox and one of the most classic designs in BMW history.Sadly, 6 months into ownership, I was T-Boned after school one afternoon by a Jeep Grand Cherokee taking a left turn. (I’m still not over it.)

Like a lot of teenage gearheads, I was entranced in modifications. As a The Fast and The Furious fanboy, I wanted to be my own Brian O’Connor in a Skyline. I wanted to stay German, as that’s what my knowledge base had grown to know best from working at the shop. With a teenager’s budget limitations, I moved to VW, a 2004 GTI with some modifications, coilovers, exhaust, tune, the light stuff. I learned a hard lesson on that one: if it seems too good to be true, it is. l dumped a lot of money and time into the VW, and after two years managed to get out from under it.

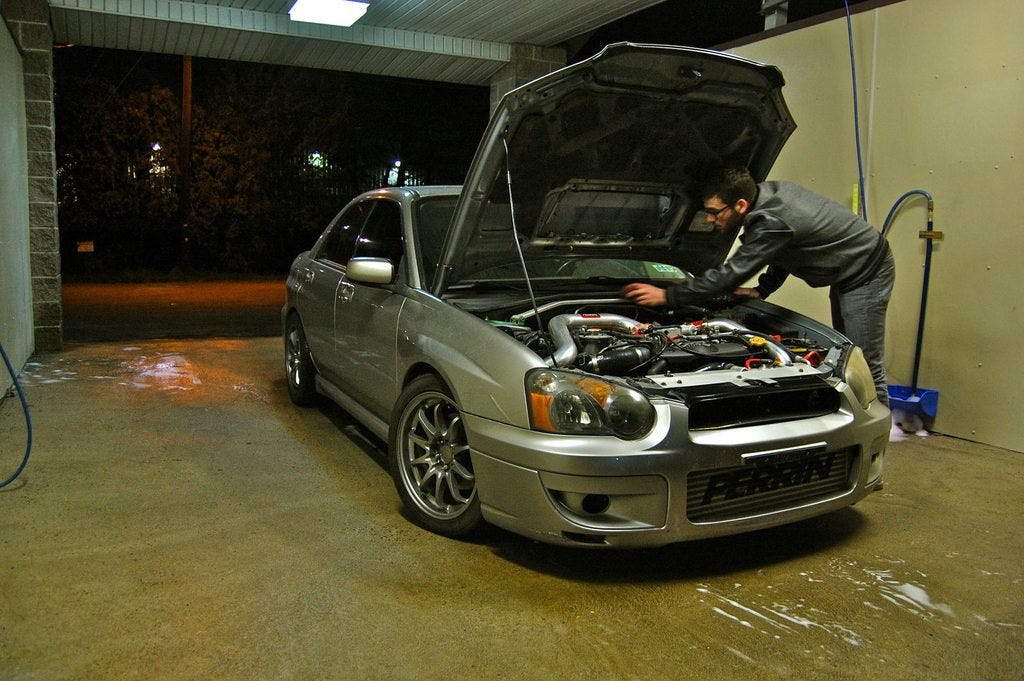

After that experience, German cars (temporarily!) left a bad taste in my mouth—I moved to Subaru. Uncle Dave had been telling me, since before the GTI, not to buy modified cars, to save the money and get something stock or nearly stock that’s capable of the performance marks you want. I should have listened to him. Instead, I bought a 2005 Subaru WRX built for rally racing. I wanted something fast, that handled well, with low miles, and AWD. The Subaru was impeccable; its previous, and only, owner was a shop mechanic who built it out with the best of the best: VF34 Turbo, 3” Invidia Turbo Back straight pipes, Grimmspeed Up pipe, Tein Coilovers, Perrin sway bars and links, 550cc injectors, Perrin front mount intercooler, Mishimoto radiator with dual fans, short ram intake, perrin brake stabilizers, Cobb tune, etc. The car was built, but I sank way more money into than I could afford. I did maintenance and had the car tuned by Decordre Performance, pushing the car to 350whp. I owned it through college and effing loved it, eventually letting go when I moved to Vermont and needed something more practical. Gas prices were also wild, and with the tune I got 8 mpg on 93 octane.

This all brings me, eventually, back to watches. More specifically, the connection between watches and cars. My uncle wore an Omega Speedmaster Automatic, ref. 175.0084. Though his Vacheron was the shiny gold apple of my eye, the Speedy was the daily driver :) These early passions formed a subconscious link—one I didn’t recognize as a common cultural one until later, especially with my own emotional wrench to screw with my memories. When Uncle Dave sold his Ferrari 360 and moved to Florida, I traded my Subaru before heading to the Vermont Studio Center as a Staff Artist fellow, and my connection to cars faded. It was a real hit for me—more than just machines, it was about the loss of family and community.

Watches, in time, brought cars back to me. Nearly a decade later, through jewelry, I fell deep in love with the watch world—the mechanics, the ties to engineering—and with it, the natural extension back to the car world. Simultaneously falling for a woman whose childhood and family life did and often still does revolve around racing only deepened the pull, turning old wounds into faded scars. A welcome surprise. Just this morning, as I sorted through old photos of his Dino, Uncle Dave and I reminisced about his Speedy, along with a friend’s Speedy Reduced. Funny how these things have a way of coming back around.

I haven’t owned anything “interesting” since high school, but our current Mazda CX-5 keeps Sloane and all her toys safe on the Taconic. J still feels the void left by a go-fast weekend car, after ten years of inheriting, three in a row, her father’s retired toy Spec Miatas. But last we checked, they don’t fit baby seats, and NYC parking is not inviting to 2-car families.

Last summer, we spotted a pristine Gen 3 Alfa Romeo Spider rolling down Rt 199 toward the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge at sunset, its passengers cruising comfortably at 45 mph, light scarves fluttering like flags in the air. Until time and money align for something I can work on myself—something affordable, with that classic Pininfarina design I miss so much from the Dino days—I have something to look forward to.

What a wonderful walk down memory lane! Those were great days❣️❣️